New and Experimental Music,

Art & Technolgy

New and Experimental Music,

Art & Technolgy

Emerging in Chicago in 2023, microplastique occupies a distinctive place within the city’s long and deeply rooted tradition of experimental and improvised music. At a time when many contemporary ensembles focus on building new instruments or developing custom technologies, microplastique has taken a different path: assembling an expansive and often unexpected palette from existing acoustic instruments, including toy instruments and small-scale sound objects more commonly associated with childhood than with concert stages.

Led by percussionist and composer Adam Shead, and joined by longtime collaborators Ben Zucker, Molly Jones, and Josh Harlow, the ensemble brings together decades of shared musical experience across jazz, contemporary classical music, experimental performance, and interdisciplinary practice. Their performances are shaped not by individual virtuosity or extended solos, but by collective listening, spontaneous orchestration, and a commitment to real-time musical decision-making. Even when the surface feels chaotic at first, the ensemble’s deeper aim is clarity: to synchronize and shape that cacophony into form.

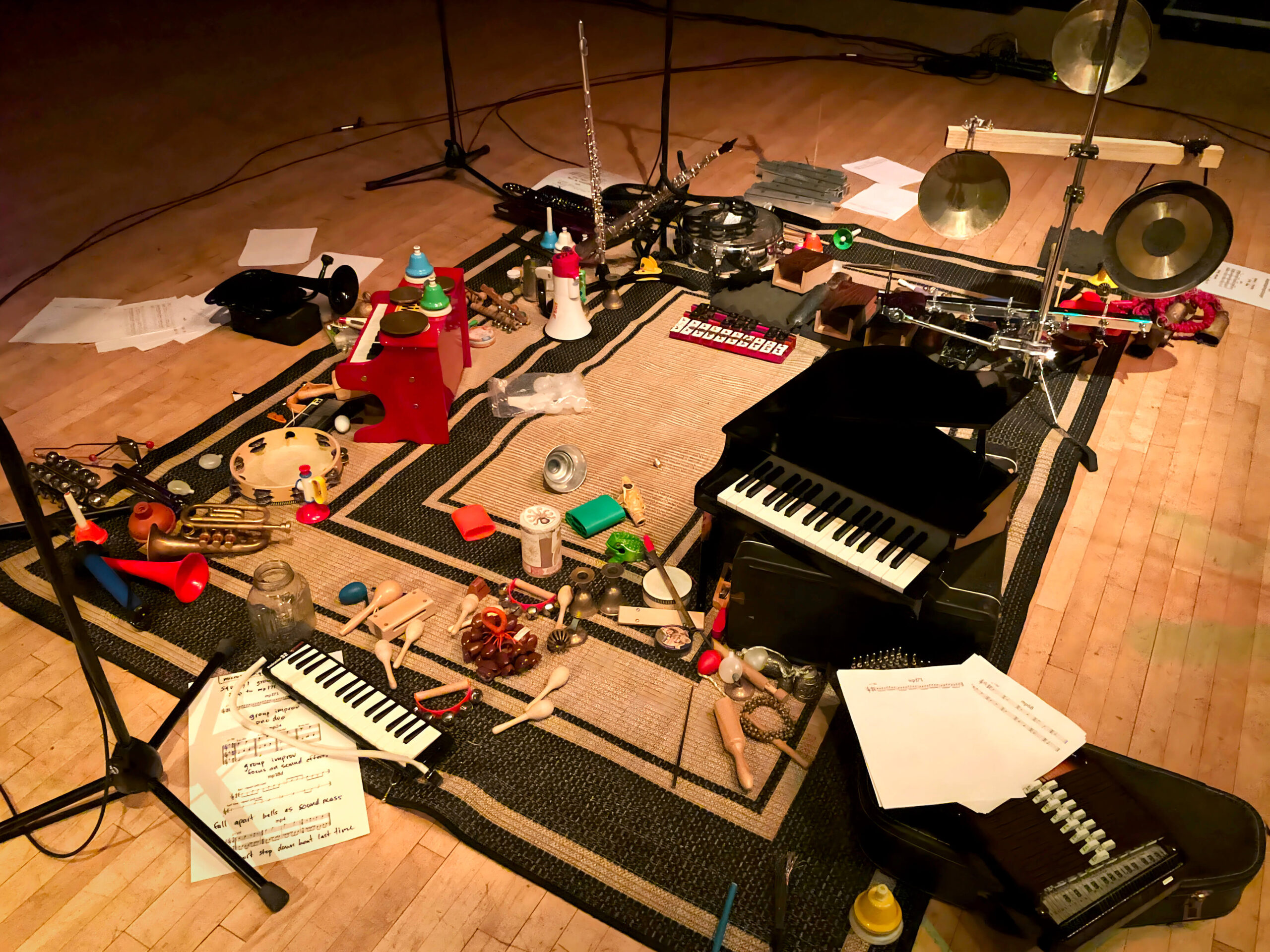

Sitting on rugs, surrounded by whistles, bells, melodicas, megaphones, percussion objects, and horns, microplastique constructs sound worlds that balance humor, absurdity, and deep musical focus. Their work draws on the legacy of the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and the Art Ensemble of Chicago, as well as on minimalist composition, folk traditions, and theatrical performance. Yet their music never settles into homage. Instead, it treats history as material to be questioned, reshaped, and reimagined.

For Shead, these influences extend beyond surface references. His compositions reflect sustained engagement with figures such as Muhal Richard Abrams, Anthony Braxton, and Henry Threadgill, alongside melodic inspirations drawn from composers like Kurt Weill. On Many Roads, the group’s second album, recorded live across six cities, these ideas unfold through short melodic frameworks that open into expansive collective improvisations shaped by place, audience, and circumstance.

In the following conversation, the four members of microplastique reflect on the origins of the ensemble, their approach to play and seriousness, their evolving relationship to instruments and electronics, the challenges of documenting live performance, and their plans for the future. Together, their voices reveal a practice rooted in trust, curiosity, and an ongoing search for new ways of listening — to each other, to their surroundings, and to the histories they inhabit.

microplastique was formed in March 2023, when percussionist and composer Adam Shead brought together longtime collaborators Ben Zucker, Molly Jones, and Josh Harlow for a project that would question, challenge, and reframe many of the conventions surrounding improvised music.

“I wanted a project to kind of poke fun at a lot of jazz and improvised music that was taking itself too seriously,” Shead explains. “While also drawing on major influences like the Art Ensemble of Chicago, Albert Ayler, and Don Cherry.” What emerged was not a parody, but a carefully shaped musical practice grounded in deep respect for tradition. Sitting on the floor, playing toy instruments, whistles, rhythmic patterns, and melodies built from a narrow range of notes, the ensemble embraces gestures that might appear unserious on the surface, while approaching them with what Shead describes as “the absolute utmost respect.”

Central to this approach is the rejection of conventional hierarchies. “It’s a group sound kind of band,” Shead notes. “There is no leader. We don’t take solos.” Rather than foregrounding individual virtuosity, microplastique emphasizes collective listening, shared responsibility, and real-time orchestration. Their music unfolds through constant negotiation among the four members, shaped by attention to texture, balance, and timing.

For Molly Jones, joining the group felt like a natural extension of her own long-standing interest in unconventional sound sources. “Adam asked me to join,” she recalls. “I’ve performed with toys for years.” She also remembers that early rehearsals included the idea of forming “four accordions,” an image that captures both the humor and seriousness embedded in the ensemble’s thinking.

Ben Zucker situates microplastique within a broader lineage of open-ended soundmaking cultivated in Chicago and beyond. Having collaborated with Shead in several projects, he recognized in microplastique an opportunity to “decenter conventional skills” and focus on performance as a holistic experience. His background in music theater and puppetry further reinforced the group’s interest in integrating visual and physical elements into sound.

Josh Harlow emphasizes the long history of shared experience among the members. “The four of us have been in each other’s orbit for the past decade or so,” he reflects. “The chance to work together in the context of Adam’s beautifully sprawling vision was an easy yes.” This familiarity allows the ensemble to operate with a high degree of trust, enabling risk-taking and rapid collective decision-making.

Playfulness, for microplastique, is never detached from discipline. “If the music is killer, you can act like a clown,” Shead insists. “But you can only act like a clown when you know why you’re acting like a clown.” Humor functions not as distraction, but as a way of opening listeners to deeper forms of engagement. As Jones observes, “Humor and playfulness live right next door to seriousness,” often allowing emotionally complex material to emerge from unexpected directions.

Zucker similarly describes moments when “deep focus and seriousness are humorous or chaotic,” arguing that sustained commitment to an idea — “committing to the bit” — can generate layered musical meaning. For Harlow, this balance ultimately reflects a commitment to sincerity: “The most genuine art communicates something about humanity and the full spectrum of what that is.”

Through this interplay of satire, reverence, experimentation, and trust, microplastique has developed an aesthetic that resists easy categorization. Their music does not seek to resolve the tension between play and rigor, abstraction and melody, or humor and gravity. Instead, it inhabits these contradictions, transforming them into a dynamic space for collective exploration.

Notably, this space remains almost entirely instrumental, though this has never been a formal rule. As Shead explains, the ensemble has “never explicitly stated” that voice should be avoided, and subtle instances of vocalization have appeared in performance and even on record. On Many Roads, for example, he points to a moment in the opening track where Josh quietly sings a melody beneath Molly’s flute—barely perceptible unless one listens closely.

For Zucker, vocal sound nonetheless remains a sensitive territory. “Once singing, let alone language, enters the picture,” he notes, “things can really take a big turn and create expectations in the audience.” Because voice carries strong cultural and emotional associations, he tends to limit its use to occasional sound effects, preserving the ensemble’s delicate balance between abstraction, play, and meaning.

One of the most immediately striking aspects of microplastique’s performances is the sheer variety of instruments and sound-making objects that surround the ensemble. Toy pianos, whistles, melodicas, stylophones, megaphones, bells, percussion objects, tape recorders, and small horns coexist with more conventional instruments, forming a constantly shifting sound palette that resists fixed roles and expectations.

Rather than treating these objects as novelties, the ensemble approaches them as materials for sustained investigation. “We all have our own collections of instruments,” Adam Shead explains, “and I have a larger collection that we share. We have sounds we want to investigate, and that takes time and repetition.” Over time, certain combinations and textures become familiar, while others are continually rediscovered through performance.

For Ben Zucker, instrumental choice is inseparable from collective awareness. “What feels appropriate or complementary comes down to our relationship to the material in the moment,” he notes. Register, density, and contrast shape his decisions as much as the physical properties of the instruments themselves. He is especially interested in “getting more out of the smaller things,” treating modest percussion objects and fragile sound sources as melodic and expressive tools.

Josh Harlow similarly frames his choices in terms of texture and direction. “I make choices based on the texture being created and the direction the sound is going towards,” he explains. Technical virtuosity, in the traditional sense, gives way to responsiveness and ensemble awareness. The guiding principle, he emphasizes, is “the best interest of the music.”

Despite their openness to unconventional tools, microplastique remains largely rooted in acoustic sound. Electronics appear only in limited, practical forms: battery-powered stylophones, small modular devices, toy tape recorders, amplified music boxes, and megaphones. “We all play acoustic instruments really well,” Shead observes, “so that’s our primary focus.” For the group, working within physical and logistical constraints becomes a creative resource rather than a limitation.

Zucker describes this approach as a way of tapping into “a spirit of the technological and mechanical” without relying on digital processing. By foregrounding touch, breath, friction, and resonance, the ensemble cultivates an intimacy between gesture and sound that remains central to their aesthetic.

In this environment, instruments rarely assume stable identities. They sometimes act as leaders, but more often as collaborators with independent musical roles that may not always seem synchronized. This forces listeners to attend to individual instruments — almost like isolated “stems” — rather than perceiving the ensemble as a unified orchestra. That tension is central to the beauty of collective improvisation. Instruments can appear to compete for prominence, only to recede moments later, allowing another voice to surface. A percussion object may function melodically, a horn may become a source of noise, and a fragile toy may carry the emotional weight of an entire section. Through constant recontextualization, microplastique transforms small sounds into expansive musical landscapes, reinforcing their belief that richness lies not in abundance, but in attentive exploration.

If microplastique’s sound palette is built from small objects and shifting instrumental roles, it is in live performance that these materials fully come alive. The ensemble’s music is not designed to deliver the same result each night; instead, it is structured to remain open—ready to be reshaped by space, pacing, and a room’s particular energy.

The group’s relationship to audience presence is complex and intentionally unsentimental. Like much improvised music, microplastique does not always aim for immediate clarity or a single shared response; listener reactions can shift widely depending on context, expectation, and attentiveness. Rather than smoothing over that ambiguity, the ensemble treats it as part of the live encounter. For Adam Shead, this means maintaining a disciplined focus on the internal life of the music—listening closely to the ensemble’s collective sound and responding in real time, regardless of audience size. In this sense, the work does not hinge on instant affirmation, but on the musicians’ ability to listen deeply, react quickly, and continually reorganize the music as it unfolds.

At the same time, several members emphasize how strongly environment can shape what becomes possible. Josh Harlow frames it bluntly: “The environment shapes everything about the moment.” An attentive audience, he explains, can help the group deliver the music “with the appropriate curiosity,” while certain elements of their library—especially the smallest and most delicate sounds—become “most effective in very resonant rooms.” In microplastique’s case, a space is not simply a container for sound; it becomes an active participant, amplifying details that might otherwise disappear.

This sensitivity to place is central to Many Roads, recorded live across six cities. Even when the ensemble maintains its own process, the practical reality of touring—fatigue, mood, circumstance—inevitably enters the frame. As Shead puts it, “It’s a different vibe in each city… it all goes into it,” even as the group tries not to let external factors “weigh too much on the music.” The balance is subtle: staying committed to the internal logic of the ensemble while allowing the moment to leave its fingerprints.

Molly Jones offers a vivid example from Lexington, Kentucky, where microplastique performed after a local improvising group whose set included props, costumes, and theatrical energy. microplastique responded with a stark contrast: “a 30-minute quiet drone using electric toothbrushes on suspended tubular bells.” The audience members who stayed, she recalls, were “clearly open to all volumes and energy levels of music,” and that openness helped the group move into new territory—an instance of how the crowd’s attention can quietly expand the ensemble’s range.

Sometimes, the live element is captured in smaller gestures. Shead recalls one moment simply: “Ben blew bubbles at a recent show. I loved that.” And audience reactions, too, become part of the performance’s afterlife. Harlow notes that listeners often leave with wildly different points of reference; his favorite sequence of comparisons came from three separate audience members: “John Faddis, black holes, and The Clash.” The comments are humorous, but they also point to something essential: microplastique’s performances invite interpretation not by offering a single message, but by creating a wide field of associations.

In this sense, microplastique’s live practice functions less like a recital and more like a continually evolving experiment—one where attention, place, and collective trust shape the result as much as the written material does. Many Roads documents these shifting conditions not as imperfections, but as evidence: proof that the music is alive, contingent, and inseparable from the moment that produced it.

If microplastique’s performances feel open-ended, it is largely because the written material is designed to function less as a script than as a catalyst. Adam Shead describes his compositions as intentionally concise—often “four to eight bars of music,” usually written as a single line, sometimes expanded into “two to three lines… a skeletal counterpoint.” These fragments act as springboards: short melodic and rhythmic cues that invite variation, re-orchestration, and collective transformation rather than fixed interpretation.

This economy of material is not a reduction of ambition but a method of generating complexity through ensemble process. As Shead puts it, “There are four of us, so we can make a lot of sound out of four measures of music.” In that sense, microplastique’s formal thinking aligns with older musical logics—theme and variation, repetition with mutation—where a small cell can be stretched into long forms through accumulated detail. Shead places this approach within a broad continuum: from early jazz and parade music to Albert Ayler, the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and beyond. “It’s all connected to the same idea of theme and variation on a melody,” he says. “That’s all we’re doing. It’s jazz.”

The group’s set structures reflect this balance between composition and spontaneity. Ben Zucker notes that performances are typically planned as sequences of these short pieces, with improvisation expected “in between,” or, just as often, with “improvisation dotted with the small compositions.” Because the written cues rarely dictate both exact notes and exact sound world, each piece remains flexible—capable of recurring across a tour while still sounding newly negotiated each night. Zucker emphasizes that the end result becomes “co-creative,” shaped as much by the ensemble’s decisions as by the notated seed.

That co-creative element is supported by a rehearsal culture that is intentionally light. Shead admits that the band “doesn’t really rehearse that much,” relying instead on each member’s background in improvisation and on the long history of shared musical relationships among them. In his view, too much control would compromise what the group does best. Rehearsals may involve concrete guidance—tempo, character, a particular cue—but once the ensemble begins “instant composing,” those plans often dissolve. “Surprise me, please,” he says.

Other members describe the cultivation of trust in more lived terms. Molly Jones points to the intimacy of touring—“sitting in a car together for hours a day”—as a practical engine of ensemble cohesion. Zucker similarly frames intuition as something built over years of collaboration and shared aesthetic values, allowing rehearsals (when they do happen) to be “technically targeted” rather than foundational. Josh Harlow distills the point: intuition comes from time together, whether spent “driving through flash floods,” going to a museum, or sharing a meal.

Even within this openness, Shead acknowledges that certain parameters guide what becomes “microplastique” material. His goal is not maximal freedom, but a particular kind of clarity: pieces that are “melodic, simple, demented, and somewhat absurd.” If a fragment falls within that character range, he suggests, “it’ll probably do well with microplastique.” And while instrument assignments sometimes happen, more often the choice remains open-ended—allowing the ensemble to discover what the cue can become through different orchestrations.

The result is a compositional practice that foregrounds possibility rather than prescription. A short line of notation can unfold into a dense, multi-layered form; a repeating cell can become a site for evolving timbre; and the boundary between composition and improvisation becomes less a dividing line than a shared working space. In microplastique, structure is not something imposed on the performance—it is something that appears through collective attention.

For an ensemble whose music is rooted in moment-to-moment interaction, the act of recording presents a particular challenge. microplastique’s performances are shaped by space, audience, mood, and circumstance; no two realizations of a piece are ever quite the same. Rather than attempting to neutralize this variability in a studio environment, the group has chosen to document its work almost exclusively through live recordings.

Their debut album, blare blow bloom! (2024), emerged as a collage of performances recorded across multiple cities. The decision to record on tour reflected the ensemble’s belief that the music’s essential character lies in its responsiveness. Each concert produced distinct interpretations of the same compositional materials, shaped by different acoustics, audiences, and collective energies. The album does not present a definitive version of the repertoire, but rather a constellation of moments—snapshots of a practice in motion.

Selecting material from this abundance required careful listening. For Shead, the guiding criteria were primarily musical: “rhythm, counterpoint, melodic development, and orchestration.” While formal coherence mattered, he emphasizes that what distinguishes microplastique’s recordings is not radical structural novelty, but the way small melodic cells and unusual instrument combinations are layered into complex textures. Depth, for him, emerges from the interaction between clear melodic material and dense, shifting orchestration.

With blare blow bloom!, microplastique first tested this documentary approach. Recorded across multiple cities, the album foregrounds contrast and immediacy, presenting short-form eruptions and rapid shifts in texture. Compared to Many Roads, its structures feel more episodic, emphasizing surprise and raw energy. In retrospect, it reads as a formative sketchbook—capturing the ensemble learning how to translate instability into recordable form.

Many Roads (2026), the group’s second album, extends this documentary approach while deepening its expressive range. Recorded across six cities during an extended tour, the album functions as both travelogue and collective diary. “Many Roads builds off the work on our first album,” Shead explains, “through further development of our group playing and understanding of each other’s sensibilities.” While the compositional framework remains similar—short melodic cues serving as foundations for improvisation—the harmonic language becomes darker, more chromatic, with greater intervallic variety.

This shift is especially audible in the ensemble’s expanded instrumental palette. The introduction of Josh Harlow’s Hohner Organa reed organ allows for sustained tones and long-form harmonic support, altering the group’s internal balance. Shead describes it as “a game changer,” enabling new kinds of continuity within the ensemble’s typically fragmented textures. At the same time, the reductionist impulse remains: melodies are still designed to be memorable and open, leaving room for the ensemble’s collective complexity to unfold.

Ben Zucker reflects on the album as an invitation to deeper listening. For him, recordings by improvising ensembles occupy a paradoxical space: they are “everything and nothing” in relation to the full experience of performance. No document can capture the totality of what happens in real time, yet each recording becomes a marker of shared attention, directing listeners toward the evolving practice behind it.

Within this framework, individual tracks offer windows into microplastique’s internal dynamics. In “Propane,” for example, multiple instruments repeatedly move into and out of prominence, creating the impression of competition without hierarchy. As one sound gains momentum, it recedes, allowing another to surface. The brass ensemble is gradually dismantled into smaller fragments over a perpetually mobile rhythmic foundation, only to be reassembled into dense, multi-layered textures. Leadership circulates, authority dissolves, and form emerges through negotiation.

Across both albums, microplastique treats recording not as a final product but as an extension of performance practice. Each release documents a particular phase of collective development, shaped by travel, fatigue, discovery, and deepening trust. Rather than fixing the music in place, these records preserve its movement—capturing the traces of a group continually learning how to listen to itself.

In microplastique’s work, small sounds are treated with sustained attention rather than novelty. Whistles, bells, breath-driven objects, and short melodic fragments are not decorative gestures but materials placed into long-form listening. What unfolds is not accumulation through scale, but complexity built through proximity: between players, instruments, spaces, and histories.

This practice depends less on spectacle than on care. Performances grow from trust developed over years of collaboration, from an ability to respond quickly and honestly to shifting conditions. Touring becomes part of that process. Repetition across cities does not stabilize the music; it destabilizes it productively, allowing familiar cues to behave differently in each space.

The ensemble’s resistance to fixed roles and solo hierarchies keeps the music fluid. Leadership circulates, textures reorganize, and instruments change function midstream. Their near-exclusive reliance on acoustic sound reinforces this immediacy, keeping gesture and result closely aligned.

The near-absence of voice plays a quiet but significant role here. By largely setting it aside, microplastique preserves an instrumental space in which meaning remains open—shaped by texture, timing, and collective intuition rather than language.

Across recordings and performances, microplastique continues to refine a practice rooted in simplicity and constraint. Short melodic cues, limited materials, and minimal instruction generate music that remains unstable by design. What persists is not a fixed aesthetic, but a method: listening closely, negotiating in real time, and allowing form to emerge through attention rather than assertion.